Architizer’s Vision Awards are back! The global awards program honors the world’s best architectural concepts, ideas and imagery. Start your entry today, and take advantage of the Early Entry prices!

Did you know that the name Archigram derives from the words Architecture + Telegram? The popular magazine was initially produced in 1961 in London. Its primary objective was to critique and overturn the strict modernist dogma that was dominant at that time through a series of unbuilt speculative architectural projects.

Peter Cook (the dynamic can-do optimist and spokesman), David Greene (the poet, pessimist, elusive dreamer and devastating critic) and Mike Webb (the hermit-like artist and design genius) were the pioneers of the magazine, followed in the second issue by Ron Herron (the positive, hands-on designer), Dennis Crompton (the back-room fixer) and Warren Chalk (the catalyst of ideas).

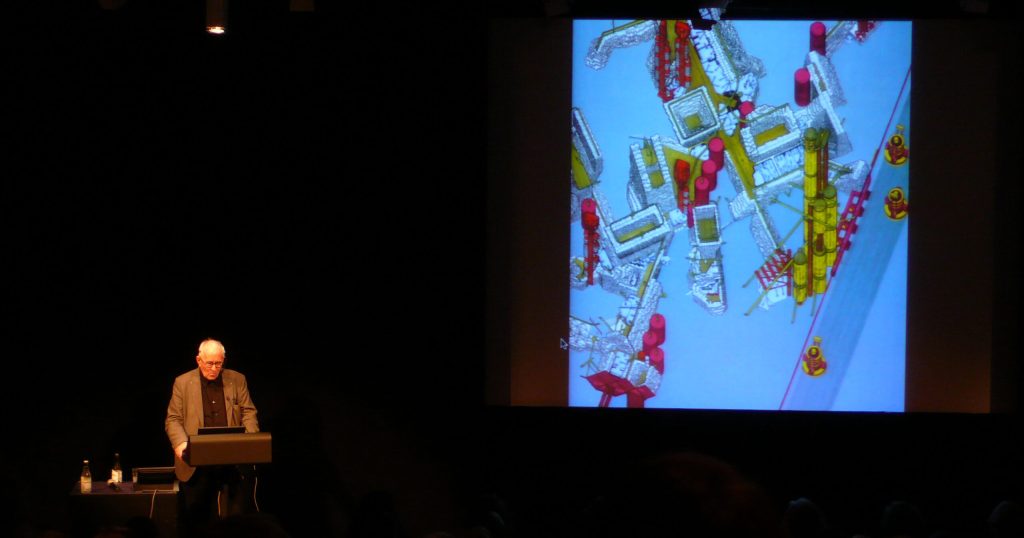

As the magazine gained popularity, the six of them worked on a series of speculative projects, drawing reference from the technologies of the “Space Race.” The Walking City, Plug-in City, Instant City and Tune City for instance, were architectural proposals comprised of pods, capsules, megastructures and infrastructures that challenged conventional buildings and proposed new modes of inhabitation and technology.

Plug-in City stood as a flexible framework upon which structures were slotted in. Instant City was a mobile technological structure that “visited” underdeveloped towns in an attempt to boost their cultural fabric, leaving behind advanced technological “plugs”. The Walking City is set within a post-apocalyptic urban setting, where cities are in ruins. It roams freely through the landscape and is comprised of intelligent robots and pods standing as a literal (and visual) interpretation of Le Corbusier’s aphorism that a house was a ‘machine for living in.’

Dune House by Studio Vural, Unbuilt

Archigram’s agenda was to critique the modernist principles that were, at that time, considered outdated and austere. The British avant-garde group delved into the post-war consumer culture, fetishized newly developed technological gadgets, employed merchandising concepts such as expandability and deliberate uselessness and most importantly gave the power of choice to the everyday consumer. Suddenly, a profession that was primarily based on notions of function, permanence and good taste, gave way to personal freedom and subjectivity. Architecturally, the speculative projects were focused mostly on structures and their countless possibilities, rather than designing stationary rooms that left little to the imagination.

In Modern Movements in Architecture, architectural critic and historian Reyner Banham wrote, “The strength of Archigram’s appeal stems from many things (…) But chiefly it offers an image-starved world a new vision of the city of the future, a city of components on racks, components in stacks, components plugged into networks and grids, a city of components being swung into place by cranes.”

Pleurotus Tower by hourdesign.ir, Unbuilt

Archigram’s influence during the second half of the 2oth century is largely attributed not only to their unorthodox proposals and the disruption of the status quo but also due to the medium through which the group chose to communicate their ideas. Specifically, by utilizing popular culture and presenting their projects through a comic-book style format (via collages and watercolor paintings) they immediately turned their work into an accessible visual narrative. Instead of producing dry architectural drawings that followed standard conventions, they chose to employ photomontage, air brush and psychedelic graphic techniques, heavily influenced by artists such as Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol and James Rosenquist.

Archigram’s success is attributed to the intentional fusion of careful architectural critique and stunning imagery. They operated at a time when architectural discourse was stifled and needed a new radical approach, both in terms of representation and attitude towards design. I would argue that today we are at a similar impasse. Ironically, the post-war consumer culture that Archigram celebrated has now become a burden for the evolution of cities: uncontrolled urban sprawl, overpopulation and profit-driven developments are some of the most challenging issues architects are currently facing. Consequently, the need for speculation, exploration and vision is more pressing than ever.

On a final note, I would like to point out a potential pitfall associated with speculative architecture projects. With such advanced digital tools in our disposal, architects may fall into the rabbit hole of producing stunning visualizations, structures and forms, without however addressing any contemporary urgencies simply relying on aesthetic criteria. This, risks reducing speculative architecture to a mere exercise in visual indulgence — detached from the very real socio-political, environmental, and economic challenges we are meant to engage with. While representation is undeniably powerful, it should serve as a means to provoke critical discourse, not a substitute for it. In this light, the most impactful visions are those that not only captivate the eye but also confront the complexities of our time with depth, relevance and responsibility.

This year, Architizer’s Vision Awards recognize this very urgency, celebrating radical ideas that go beyond aesthetic experimentation to meaningfully shape the future of the built environment. By inviting imaginative urban solutions, groundbreaking housing models, and speculative public architecture, the awards champion projects that use visionary thinking as a springboard for innovation.

Architizer’s Vision Awards are back! The global awards program honors the world’s best architectural concepts, ideas and imagery. Start your entry today, and take advantage of the Early Entry prices!

Register for the Vision Awards

Featured Image: “ECO LOOP” COAF SMART Campus in Armavir by URBAN UNIT Architecture, Unbuilt