Talent is overrated in architecture and it means that other, more important qualities tend to be overlooked, writes Matthew Bovingdon-Downe.

Architects are obsessed with talent. Despite our awareness of the busily collaborative nature of our work, of the many hands needed to bring it about, we remain determined to single out individuals for special mention. We seem incapable of assessing the relative merit of projects without pinning them to personalities.

This tendency to acknowledge the herald over the deed is a hangover from the Renaissance, a legacy of the humanist arrogance to presume ourselves at the centre of things. The idea of artists and architects as rare or exceptional types – and the consequent tendency to self-glorification – is something we haven’t quite managed to shake off.

Architects are genteelly dismissive of graft

When we celebrate individual talents we, as architects, celebrate ourselves. Mixed into our obsession with talent is the oil and vinegar of idolatry and self-regard.

With the gradual, if occasionally faltering, progress of social democracy, one would expect this kind of thinking to fall out of favour. But it persists, laundered, rehabilitated in the form of awards schemes aimed at highlighting the work of individuals and recruitment initiatives on the hunt for talent, diamonds in the rough.

Take the AJ100 New Talent Awards, for example. There to acknowledge the contribution of assistants and newly qualified architects – nominated by their respective practices, one suspects in lieu of promotion – these awards open up the discourse to allow for the presence of people whose efforts would otherwise go unnoticed.

Well deserved, I’m sure. Good publicity for the practices mentioned. And rather cheerful, as editorial conceits go. But awards of this kind are clearly a symptom of our tendency to disaggregate the combined efforts of many diligent, committed people, in order to create arbitrary distinctions in value.

Talent has become a rather crude shorthand for the many and varied contributions people make to the architecture industry. The common denominator is in fact effort, but architects are genteelly dismissive of graft. It doesn’t suit our cerebral, elevated idea of what we do. We prefer instead to dignify, mystify, or sex up it up.

Talent is sexy, after all. Sexier at any rate than diligence and industry, or the coordinated efforts of large numbers of unnamed, uncharismatic, or insufficiently photogenic people.

People generally become good at things by being bad at them for longer than the rest of us would cope

When we speak of talent, we tend to mean the innate or adventitious type. The type that carries connotations of divine endowment. People are talented in the same way that people are good looking. It’s genetic. They’re naturally gifted.

Of course, this conception fails to account for the degree to which talent stands as an index for opportunity. Sure, some people benefit from what might be called natural propensity. But the extent to which these propensities are cultivated, eked out, often depends on their being allowed the time and resources necessary.

It also invalidates the role of effort in our achievements. If you’re not good at something it’s probably because you’re not talented, and so you don’t need to work hard.

The truth is more instructive. People generally become good at things by being bad at them for longer than the rest of us would cope before being put off. Bad news for wannabe wunderkinder, but great news for budding architects.

While our mania for insta-hits and overnight reputations persists, architecture entails a slow burn. To be a half-decent architect, you don’t need to be any good at the outset. You can take your sweet time to percolate, to ply your craft, to perpend.

The meritocrats among us seem determined to claim architecture as “a career open to talent”, regardless of whether it requires those talents in practice. This is both self-gratifying, since it implies – wrongly, as it happens – that those already working in architecture are necessarily talented; and it is wrongheaded, in that it discounts those people who might have other, perhaps less scintillating qualities.

You don’t need to be talented to work here, and neither is it likely to help

It can count only as progress that there are now more opportunities advertised to those from underrepresented backgrounds. According to the ads however, there’s a catch: we seem only to want “talented” people. Talented people from marginalised communities. Talented people we don’t typically hear from.

It begs the question: why, if we’ve taken steps to make the profession more accessible, do we slap arbitrary new restrictions on it? Most architects lead lives of a healthy, unobtrusive mediocrity after all – never having been sanctioned as talents, never having the neck to fake it.

Besides, recruitment isn’t the problem, it’s retention. Why lure self-consciously talented people into the workforce, when most architectural graft is a conspiracy against the cultivation of individual talent?

Most tasks, let’s face it, don’t call for talent anyway. Our functions are broadly clerical, involving little more than the dutiful transcription of already-decided-upon details. Given the opportunity, anyone could do it, eventually.

Doing it well is another question of course, but even that doesn’t require talent per se. Talent is a nice thing to think of an architect as having, but it isn’t at all necessary. You don’t need to be talented to work here, and neither is it likely to help.

Architecture isn’t really something you can be talented at. It’s too combinatorial, too contingent. You’re too dependent on other people for it to come off.

If we want to make meaningful steps to progress, we’ll need more than talent

I’m not saying talent is everywhere unwelcome, but the fact is it counts people apart. It leads us to prize eminence over integration. To ham up how damned special we are, and not how involved, how implicated in the discipline we might become.

Widening participation will result in a welcome influx of talent, no doubt. But architecture, like other social endeavours, calls for diverse qualities. If we want to make meaningful steps to progress, we’ll need more than talent.

When we think of architecture, we must ask ourselves whether we want it done by the most talented, or the most committed, cooperative, diligent, resourceful, considerate. Talent is overrated.

Matthew Bovingdon-Downe is a designer and writer based in London.

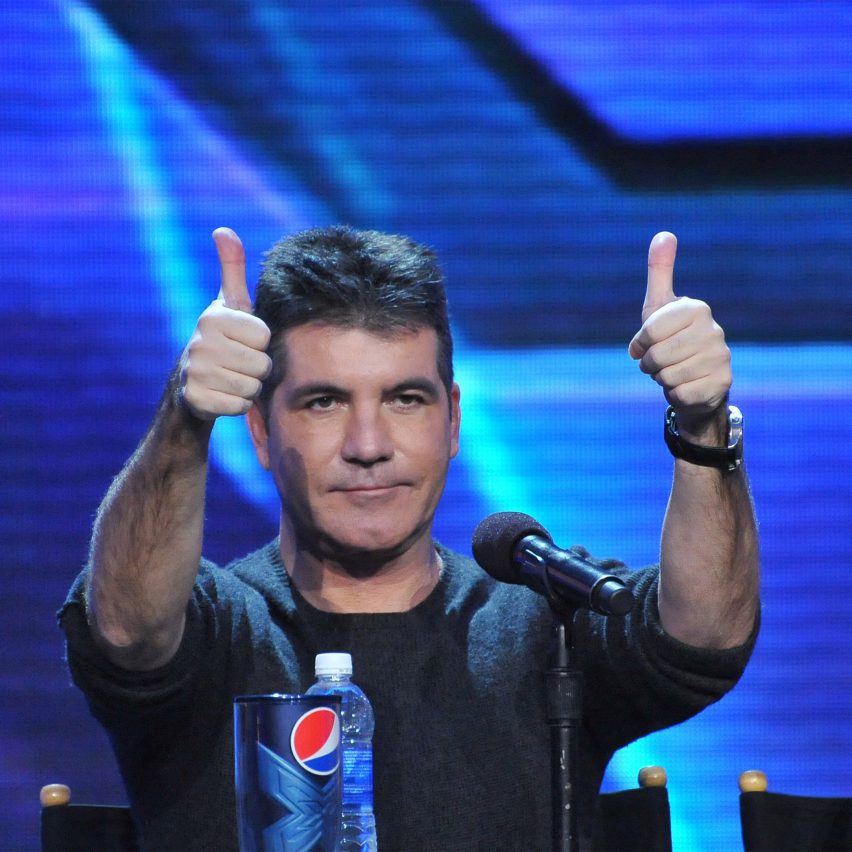

The photo is by Featureflash Photo Agency via Shutterstock.

Dezeen In Depth

If you enjoy reading Dezeen’s interviews, opinions and features, subscribe to Dezeen In Depth. Sent on the last Friday of each month, this newsletter provides a single place to read about the design and architecture stories behind the headlines.

The post "Architects are obsessed with talent" appeared first on Dezeen.