Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work by uploading projects to Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

As porous as this stone is the architecture. Building and action interpenetrate in the courtyards, arcades, and stairways. In everything they preserve the scope to become a theatre of new, unforeseen constellations.

– Naples by Walter Benjamin and Adja Lacis, 1924

Drawing a parallel between Naples, as described in an essay written by Walter Benjamin and Adja Lacis in 1924, I would characterize Athens as equally porous, albeit in its own rough and unrefined way. It is a city that boasts a unique culture of intimacy, which permeates public life, especially in the densely populated city center. Courtyards become interior voids between polykatoikias (multistory buildings), and arcades become narrow, one-way streets that confuse anyone who ventures through them. At the same time, stairways are replaced by ground-floor balconies that spill onto the sidewalks.

In the 19th century, when Greece gained independence, Athens was almost entirely in ruins. Without an established governmental mechanism to impose specific rules on land ownership and urban organization, individual landowners collaborated with contractors and architects to address the pressing housing problem. Eventually, the extensive influence of the Modernist movement in the 1920s reached Athens; its ease of replication on a small scale meant that the broader Athenian social strata embraced the movement with enthusiasm.

Left: G. Psaltis, Map of Athens, 1890. Right: Blue Apartment House, Athens. Both marked as public domain, more details on Wikimedia Commons.

Despite the many complaints regarding the dominance of ‘the concrete, modernist, “ugly” polykatoikias’, Modernism was subconsciously chosen by the general public. Its success can be attributed precisely to its small-scale application and a kind of participatory design process that was not orchestrated by the state but instead was self-organized by small players: the landowners, contractors and architects. The fragmented land ownership also hindered the realization of grand modernist urban visions, such as wide boulevards, monumental buildings and vast parks. Instead, the Athenian version of Modernism has produced a compelling social space, which continues to attract considerable interest from both researchers and the international public.

Currently, two trends are emerging in Athens. On the one hand, large-scale projects are being developed on the periphery, following the tradition of “orthodox European and American Modernism,” prioritizing profit, attractiveness and technological “flamboyancy.” On the other hand, a new generation of architects is intervening with small-scale projects within the urban fabric, maintaining the unique (intimate) character of Athenian Modernism.

Three project narratives now take center stage, each one presenting a different interpretation of what it means to design intimately within a modernist setting.

Akra

By Myrto Kiourti, Athens, Greece

Akra by Myrto Kiourti, Athens, Greece

Stepping into Akra, we are immediately transported into a domestic spatial concept that operates within the scale of the city. The restaurant was designed as a reinterpretation of the typical kitchen found in a modern home, which was widely common among post-war middle-class Athenians. The reference to the domestic kitchen is not about specific forms, but rather about a subconscious resonance between bodies in space.

In Akra, the entire cooking process takes place on kitchen counters that surround the dining area. The tables are positioned very close to the counters. Diners watch the chefs as they cook with their backs turned, much like children observing their parents at home. The sense of intimacy is intensified through the choreographed actions of two specific people—the two head chefs who are there every day. They use architecture as a means to express their vision, where elevated gastronomy is generously offered to all people, regardless of their origin, much like the care of parents. They experience the space as their own home; they say, ‘Here, we eat as a family.’

Tavros

By AREA, Architecture Research Athens, Athens, Greece

Tavros by AREA, Architecture Research Athens, Athens, Greece

The neighborhood of Tavros, in Athens, is named after the mountain range in southern Turkey from which a wave of immigrants arrived and settled in the 1920s. The new Community Art Space, curated by the Locus Athens team, aspires to function as an “open and democratic space,” forging relationships with artists of diverse backgrounds, as well as with the local community itself.

Located on the first floor of a building housing artisanal workshops, Tavros is a part of the modern city: an open and continuous space defined by concrete columns and beams. It is inhabited by a curious object: a movable, lightweight, and playful oversized piece of furniture that changes according to need or whim. A colorful curtain travels with the object, sometimes concealing and sometimes revealing the functions of a large, suspended table: a place for a workshop, a presentation, an informal meeting, or just a desk. The minimal and ephemeral nature of the intervention draws on the area’s refugee history. As the steel structure migrates, its relationship to space changes, forming new organizations and hierarchies, and allowing new events and exhibitions to take place.

BIOS Hub

By FLUX office, Athens, Greece

BIOS Hub by FLUX office, Athens, Greece

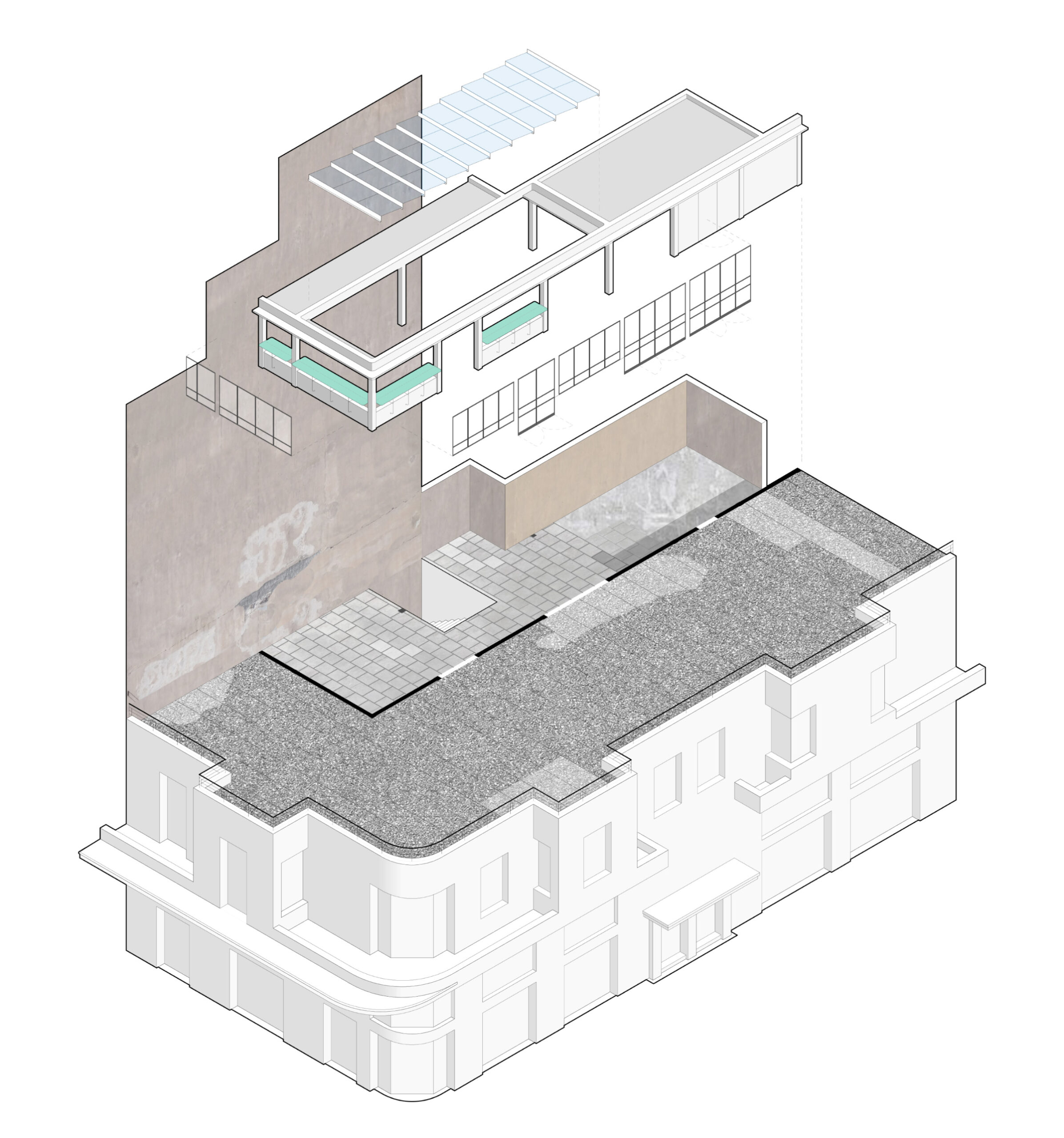

Initially a leaf spring factory, with workshop and office spaces, Bios Hub is a space situated within a mid-war era industrial building, designed in 1935, by architect Athanassios Demiris. Now, many years later, it has taken the form of a cultural and creative space, always, however, maintaining a close notional and material proximity to the distinctive character of the original building. The architecture is intimate, both in terms of the amount of detail put into every design decision and also in terms of the overall “understanding” of the space.

Specifically, the space is treated as a set, where the design is directed by multiple script re-readings: what is the story behind the Bios rooftop, which used to accommodate an old laundry room, a storage area and a stairwell? How does the light behave within the space? What are the objects found within? And — most importantly — how many “moments in time” does the particular space hold? This layered approach imbues Bios Hub with a sense of intimacy, where space, memory and narrative intertwine to create a living archive that evolves through use, atmosphere and attentive design.

Intimacy by Design

BIOS Hub by FLUX office, Athens, Greece

Intimacy may reside in the design process. It may also exist in relation to the protagonists of a space or even to the broader city. It romanticizes a rather austere and rule-driven design approach. It rejects the concept of “over-design,” creating possibilities and opportunities that are open for interpretation, celebrating the present complexity of the Athenian urban fabric.

In a time of increasing detachment and displacement, the most radical gesture an architect can make is to design something truly, quietly intimate. In Athens, this intimacy emerges from the cracks of an unplanned city, in the improvised social contracts between balconies, courtyards and arcades. But the question it raises is universal: how can architecture resist alienation, not through grand gestures, but through care, attention and the space it gives for life to unfold? As cities across the world grow more generic and spectacle-driven, the Athenian case reminds us that meaningful architecture can also be small, temporal, and unresolved. Intimacy, then, is not simply a scale or a mood — it is a political and ethical stance.

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work by uploading projects to Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.