The winners of the 13th Architizer A+Awards have been announced! Looking ahead to next season? Stay up to date by subscribing to our A+Awards Newsletter.

A portal. The fourth actor. A physical manifestation of emotional space.

Such are some of the ways the theater stage has been described. Situated between film and architecture, the design for a set is a balancing act. Albeit immersive, film sets are not tangible nor accessible, viewed through the “glass screen” filter. On the other hand, architectural space is often experienced at such a subconscious level that it is almost overlooked. Theatre sets are both temporal and structurally sound, emotional and functional, fictional and practical. They are spaces for performance and expression, designed, however, with an incredible amount of detail to ensure they are functionally sound. Consequently, if architecture is built for forever and film for the frame, is it the theater set that dares to build for the soul?

Buried under building codes, regulations, budgets, and the pressure for permanence, architects are often stifled by such limitations, opting for pragmatic, functional solutions instead of emotive ones. Countless skyscrapers, civic buildings, suburban blocks, etc. are built with practicality and convenience in mind, dismissing any effort for spatial expression. Set design, however, always begins with a story. The script is the steering compass that dictates the look and feel of a stage. It sets the chronological timeline, the season, the time of day, the characters and their emotions, and their dialogues, even before introducing the physical aspects of the space, such as the program, or the objects occupying it.

The Merchant of Venice, Stage Design by Lot71, llc, Denver, Colorado

Ralph Koltai, one of the most influential British stage designers of the 20th century, treated the set as the “fourth actor.” His designs were often sculptural and emotionally charged, acting as spatial metaphors for the lives of the characters. Specifically, his design for Jean Genet’s The Balcony, 1960, was constructed from tall iron scaffolding. His deliberate use of metal symbolized power and entrapment, conveying feelings of restriction and suppression to the audience. Later in his career, he worked with steel, concrete, and wood in their rawest form, in an attempt to create a space that delivered a performance in itself.

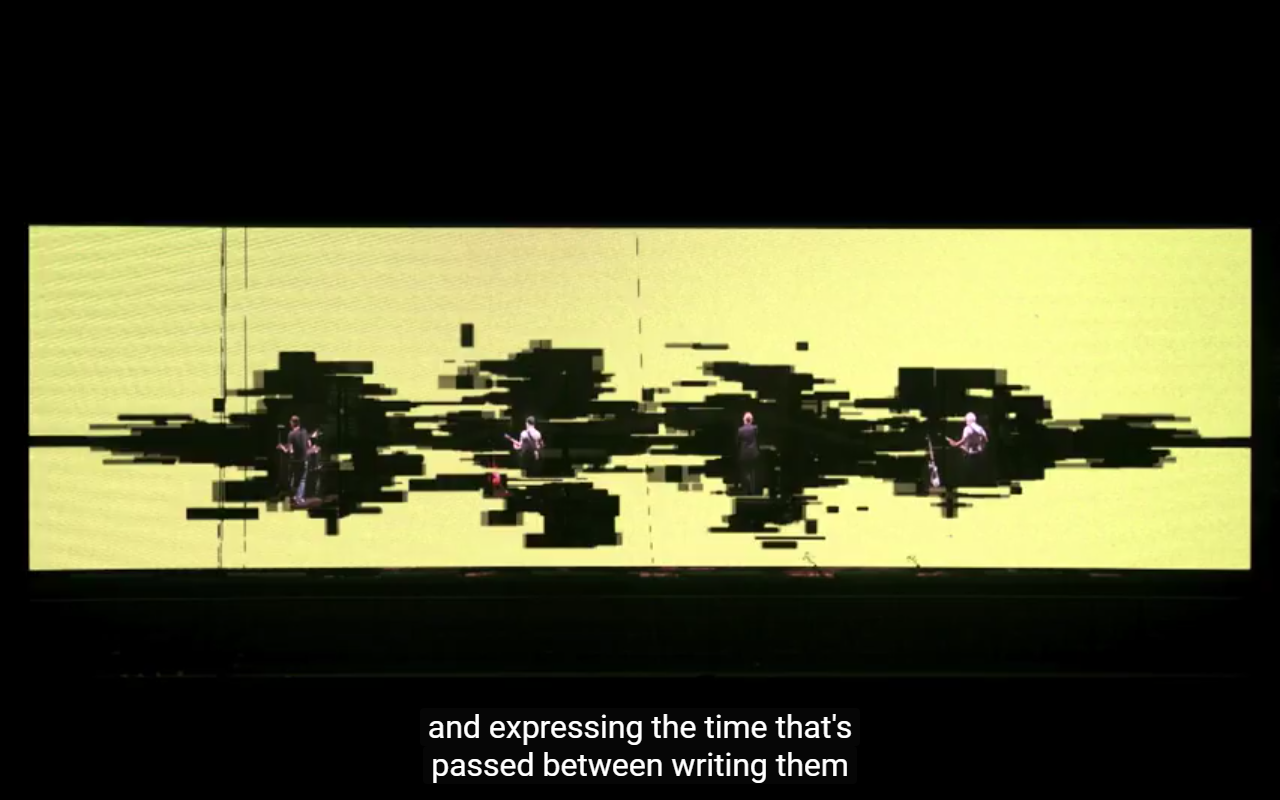

Stepping into the contemporary stage, Es Devlin is perhaps one of the most sought-after stage designers of our time. Following an interdisciplinary approach her work is found between art, architecture, theatre and installation, creating sets that warp, bend and manipulate space, time and emotion. Her stages are considered “metaphysical landscapes,” using forms as symbolisms rather than functions. For example, the Lehman Trilogy play is set inside a minimalist, rotating glass cube, which serves as a bank, a home, and a void that bends the rules of time, memory, and identity. Her designs are interrogatory, dynamic and resonant.

Nesta and Es Devlin, Es Devlin U2 and Bono at O2 band, CC BY 3.0

Perhaps the one typology of buildings where theater design is spilling into the field of architecture is cultural centers, where experience, immersion and narratives are equally crucial with function and practicality. For instance, in 2009 Rem Koolhaas designed the Wyly Theatre in Dallas, radically rethinking what a theatre can be. The building itself comes to life, operating as a spatial machine that shifts the stage and seating, completely eliminating the traditional theater layout. For Koolhaas, the theatre serves as an extension of the stage and, consequently, the performance itself.

In contrast, other architects, such as David Rockwell, have stepped directly into the world of scenography, drawing, however, from their architectural philosophy and practice. Rockwell’s designs for Hairspray, She Loves Me, and Kinky Boots are based on the approach that space should evoke emotion, connection and intimacy. His architectural background allowed him to study the stage in a three-dimensional way, setting him apart from other designers.

Additionally, his use of light, apart from conveying intensity and atmosphere, aims at adding depth to the design, creating layers of spatial meaning that shift and evolve with the performers’ movements. At the same time, Rockwell’s commercial spaces also showcase an immense level of theatricality. Although more static, his designs for hotels, restaurants and commercial spaces are imbued with a strong sense of drama and narrative, utilizing elements such as bold lighting and choreographed circulation.

Kinky Boots by Rockwell Group, New York City, New York

Theater design essentially amplifies the spatial storytelling that architecture is intended to embody. Architecture on the other hand, bears the burden of permanence, functionality and regulation. Yet, through this burden, it gains the power to shape daily life and leave lasting cultural legacies. Still, this in-between zone that exists between the two disciplines redefines space in terms of its ability to transform, move and direct. It no longer matters if a space is permanent or performative but rather that the one borrows from the other, transforming a theatre stage into an architectural laboratory and a piece of architecture into a stage set in its own right.

The winners of the 13th Architizer A+Awards have been announced! Looking ahead to next season? Stay up to date by subscribing to our A+Awards Newsletter.

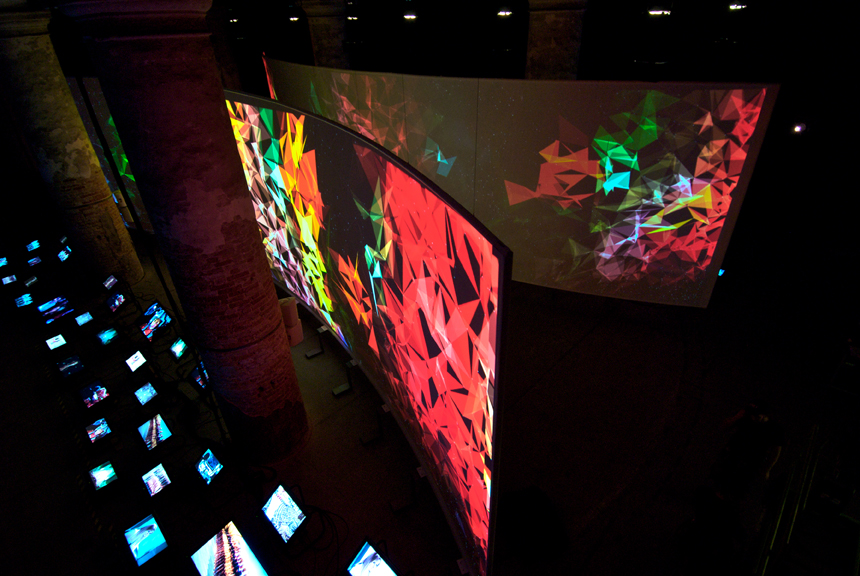

Featured Image: Hall of Fragments, Venice Architecture Biennale by Rockwell Group, Venice, Italy