Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work by uploading projects to Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

Material choices are a major part of every project. From travertine to limestone, corten steel to zinc, timber to terrazzo, architects spend a huge amount of time and energy selecting the perfect materials for their designs. Unfortunately, not all the materials used in a project are chosen. Some force their way into the built environment, not through design intent but through sheer industrial excess.

In times of need, the world has always turned to architecture to discover various inventive ways of absorbing industrial byproducts. The Romans strengthened their concrete with volcanic ash because it was abundant and a nuisance. In 19th-century Northern Britain, slag bricks, otherwise known as Scoria brick, were manufactured as iron production ramped up. Their dense, blackened surfaces were a direct product of the abundant steelworks waste of the age.

When the Second World War left European cities in ruins, reconstruction relied on crushed rubble and salvaged materials. Cities like Warsaw, Rotterdam and Berlin remade themselves from their own remains. While in Britain, bomb-damaged buildings were pulverized and re-formed into new bricks, recycling history into the next iteration of the city. For centuries, “ghost materials,” which are produced inadvertently through industry, have been just as much a part of construction as any consciously selected stone or metal. Ghost materials take what is leftover and unwanted and give it purpose.

Right: Cakelot1, Whitby Scoria Bricks 1, CC BY-SA 4.0 | Left: Photo of Scoria brick in York taken by author.

The construction industry is one of the largest producers of waste materials, so architects and builders are increasingly looking for smarter ways to reincorporate their waste into new structures. Demolition rubble is being crushed for aggregate, while discarded concrete is recast into precast panels. Old bricks, once considered too labor-intensive to salvage, are now cleaned, sorted and reused at scale. Meanwhile, timber offcuts and sawdust are compressed into structural elements and insulation.

Materials that were once difficult to recycle are also making their way back. Contaminated plasterboard waste can now be processed and remade into new gypsum panels. Rigid foam insulation, often stripped out during renovations, is salvaged rather than replaced. Even offcuts of cross-laminated timber (CLT) and laminated veneer lumber (LVL), previously considered too complex to reuse, are being reassembled into new engineered wood products instead of going to waste.

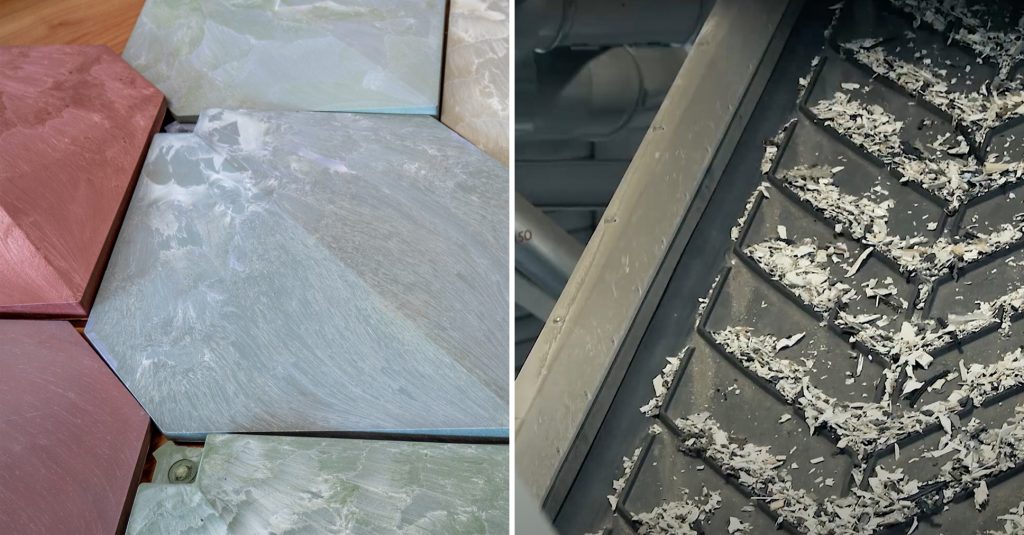

FRONT’S Pretty Plastic Panels | Photo by Nienke Krook courtesy of FRONT

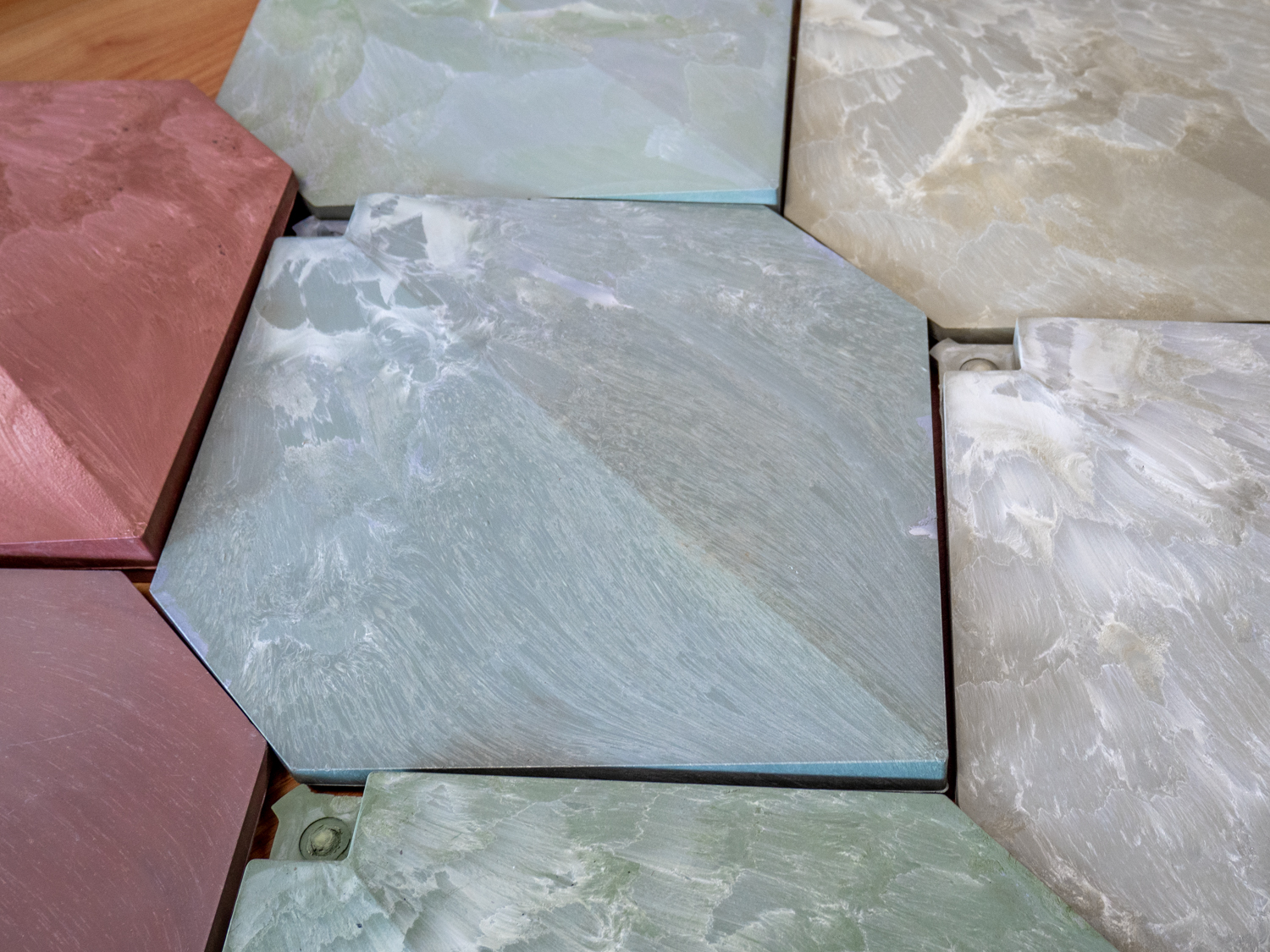

Companies like FRONT are finding new ways to return construction waste back into the built environment. Their WasteBasedBricks are made using demolition rubble from urban deconstruction sites and give a second life to materials that would otherwise be crushed into low-grade aggregate. Their Skip Tiles, composed of 95% recycled ceramics, reuse discarded offcuts and broken tiles from tile manufacturers, reducing the waste produced in fabrication. Even PVC waste from construction sites, previously difficult to recycle due to its chemical composition, is being repurposed into Pretty Plastic Panels, a cladding material for ventilated façades and rainscreens.

Ghost materials may be becoming more popular, but their unreliability is the main reason they remain secondary materials rather than primary ones. Unlike quarried stone, precision-mixed concrete, or engineered timber — each manufactured to strict tolerances — construction byproducts can be inconsistent, chemically unstable, and difficult to standardize. The challenge is not just how to integrate them, but how to account for their unpredictability.

Recycled concrete aggregate (RCA), for instance, should be an easy substitute for virgin aggregate. In practice, its variable porosity, residual cement content and embedded contaminants make it difficult to control. Old concrete often contains alkali-silica reactions (ASR), which cause unpredictable expansion and cracking in new concrete mixes. Water absorption rates are higher than in natural stone aggregates, meaning RCA must be used in carefully controlled proportions to prevent shrinkage and structural instability. Unless tested batch by batch, no two recycled concrete aggregates behave exactly the same. In the Netherlands, New Horizon Urban Mining has been tackling this issue by developing methods to extract and refine RCA with greater consistency, allowing it to be used more reliably in structural applications.

Anne & Max, Haarlem, Netherlands | FRONT’s Waste Based Bricks, Glazed Bricks | Photo by Sheena Schouwink courtesy of FRONT

Recycled gypsum presents similar challenges. While the material itself is infinitely recyclable, plasterboard waste is rarely clean. It often contains paper fibers, residual adhesives, fire retardants and even contaminants like lead paint or mold spores, depending on its source. When reprocessed, these impurities must be removed or stabilized. A time-consuming and costly process that makes virgin gypsum the more attractive option in many cases. In the UK, British Gypsum has introduced a closed-loop recycling system for its plasterboard products, ensuring that offcuts from construction sites can be collected, cleaned and reintegrated into new gypsum board production with minimal loss of quality. However, this only works when waste is carefully separated on-site. Once mixed with general construction debris, plasterboard becomes too contaminated to recycle.

Timber presents its own set of issues. Reclaimed wood, especially from demolition sites, is prone to warping, uneven moisture content and historic chemical treatments that may be unsuitable for indoor use. Timber offcuts from modern manufacturing, such as CLT and LVL remnants, are structurally sound but irregularly shaped, making them difficult to integrate into conventional framing systems. This is why many wood byproducts are compressed into chipboard or engineered panels rather than reused in their original form — not because they lack strength, but because they lack standardization. In Germany, Gutex has developed a system to turn sawmill byproducts and wood-processing waste into high-performance wood fibre insulation, an approach that ensures even the smallest timber remnants are used in a meaningful way.

Then there is the issue of regulation. Most building codes are still based on materials behaving in predictable ways. A steel beam has a known yield strength, a fired brick has a consistent compressive strength, and a concrete mix is designed to cure to a precise specification. Ghost materials, by contrast, come with unknowns. Recycled aggregates often face lower structural classifications because their past life affects their long-term performance. Reclaimed steel is subject to stricter inspection standards than newly forged beams, even if its metallurgical properties are identical. Recycled plastics are rarely approved for load-bearing applications because their molecular structure degrades with each recycling cycle, introducing brittleness over time.

This regulatory hesitation may be seen as bureaucratic resistance but in reality it’s a necessary safeguard against structural failure. Materials with unknown histories or variable performance characteristics introduce risks that architects and engineers cannot always quantify. While this does not mean ghost materials are unsuitable for construction, it does mean that architecture must rethink how it designs with them.

FRONT’s Pretty Plastic Panels | Photo by Nienke Krook courtesty of FRONT

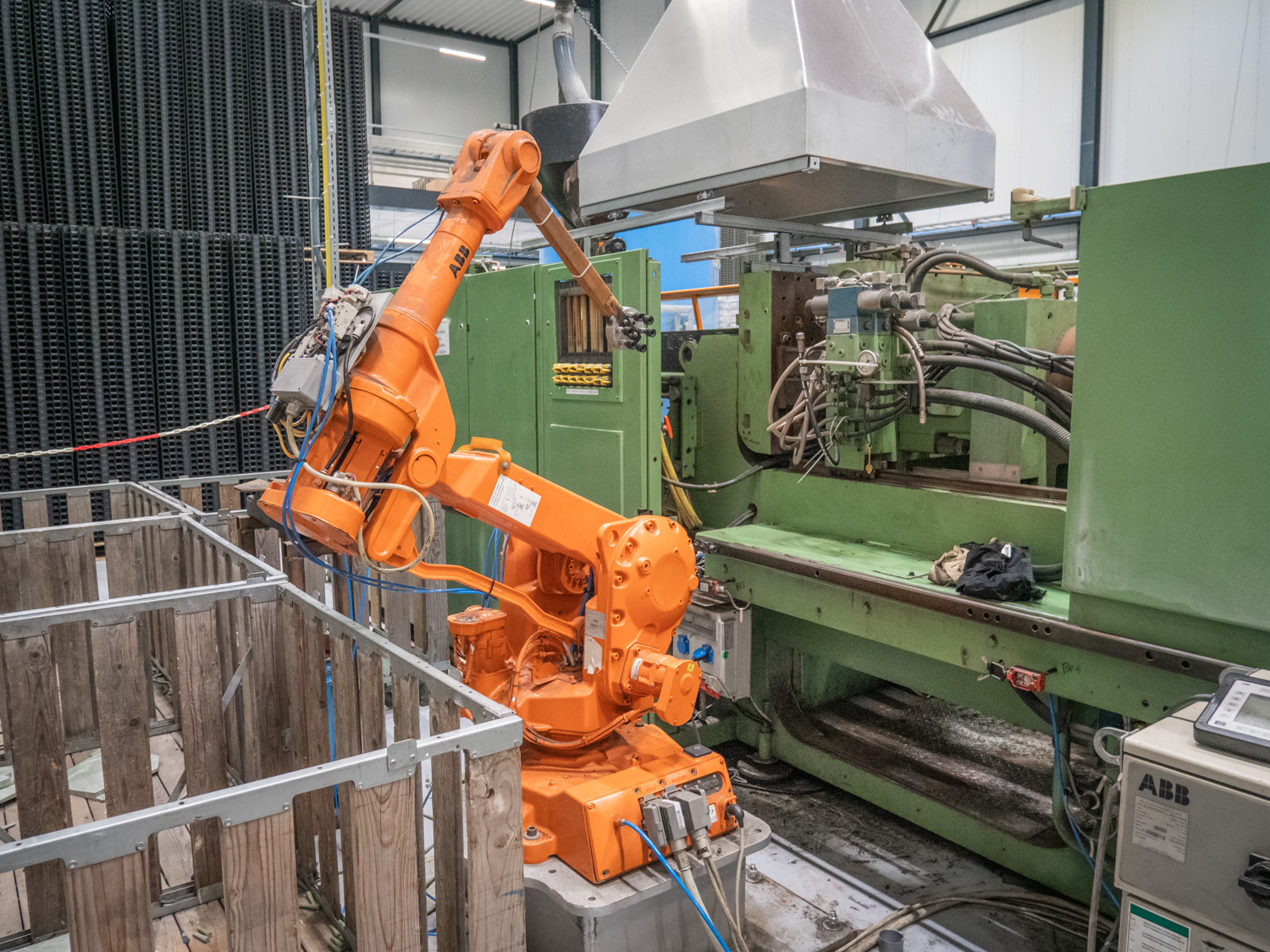

At ETH Zürich’s Digital Construction Lab, researchers are exploring how robotic fabrication can create highly precise structures from irregular recycled materials. Instead of treating reclaimed elements as defective, their approach uses digital modelling to work with material inconsistencies, enabling them to fit together seamlessly in a controlled construction process. This method reduces waste and ensures that each component is used efficiently rather than being discarded for failing to meet traditional industrial standards.

The reality is ghost materials are an excellent way to reduce the excessive waste in the construction industry. As material shortages and environmental concerns push us towards circularity, architecture is being asked to engage with them in a new way. The question is no longer simply how to repurpose waste, but how to build with it intelligently and safely.

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work by uploading projects to Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

Top photo: FRONT’s Pretty Plastic Panels courtesy of FRONT